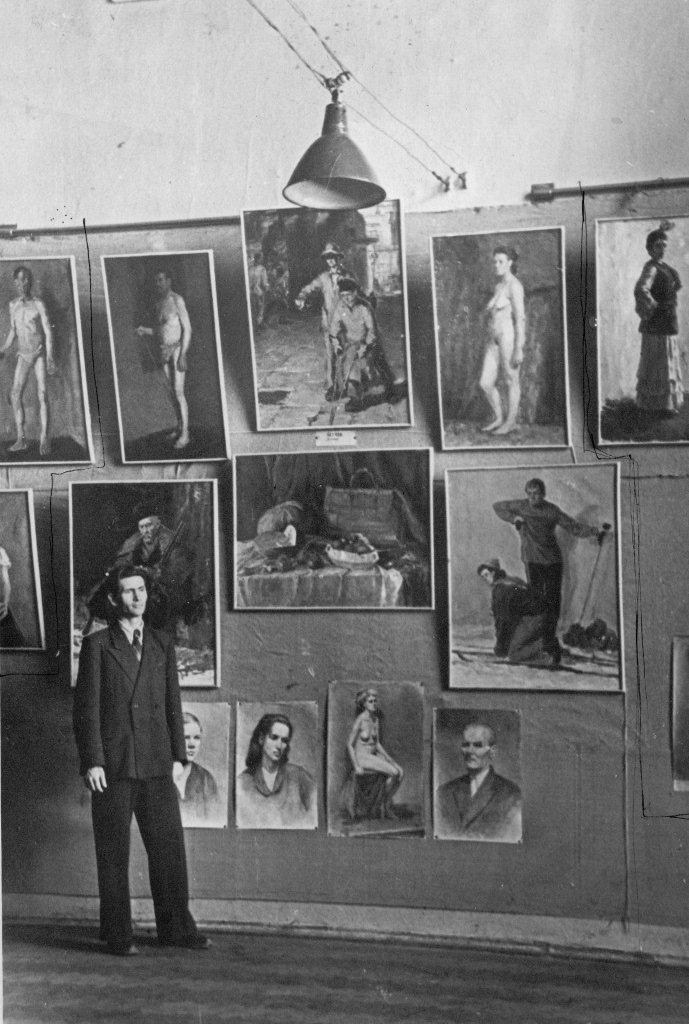

Chetkov and his thesis work, 1959

In 1960 Chetkov returned to Leningrad to enroll in art school again. However it became a torturous process. His style was too forthright, too developed: “It is always tough to teach someone who is already educated. It is better and easier to take students from high school, to shape them the way they want. Teaching me demanded an effort: maybe I would need extra work, special studies. They didn’t know what kind of person I was either. What if he is stubborn? There’s no place for him here.”

In another moment of sheer serendipity – which also shows Chetkov’s incredible ability to live in the moment, and to see its potential – he met the Director of Admission from the Stroganov University of Arts. Director Voloshin took one look at Chetkov’s work and told him to come to Moscow. After passing his entrance exams with flying colors, Chetkov entered the textiles department before later transferring to ceramics and glass. This was a very happy time in Chetkov’s life. He said, “I studied and felt completely at home, I was friends with professors. I got excellent grades. I went to museums with my professors. We used to talk about art and creativity.”

The head of the department was Vladimir Vasilyev, an avant garde artist who had achieved some prominence in the 1920s. While under his protection Chetkov gained excellent grades. However in his last year Vasilyev died and was replaced by a zealous Communist Party member, Seleznev. “A couple of times after Seleznev’s appointment I noticed a student standing behind a column and scribbling something in her notepad while I was discussing art and, in unflattering terms, Socialist Realism.”

After surviving the Gulag, World War II and a near-fatal disease, something as minor as the disapproval of the Communist Party barely checked Chetkov’s stride. He continued to discuss western art movements, to paint as he wished and develop as an artist without reference to ideology. But the party increased his efforts against him and the writing was on the wall. Seleznev was trying to get approval from the university board to have all of Chetkov’s excellent grades removed and downgraded to fails, thus in a stroke removing him from the university and rendering his years of study null and void. Fortuitously the head of another department pulled some strings and got him transferred to Mukhina School of Arts in Leningrad to finish his last year. Chetkov left without looking back.

Even here it was touch and go; harried by the Communist Party, he barely scraped by: “At the autumn exhibition, my works were painted over; my paintings and drawings were marked with a mere 3 (C). However, I was allowed to uphold my diploma, even though my fellow communist students were clearly not happy about it.” The final comment on his five years of work was, “he is not an artist but a good craftsman.”

Courtesy Kenneth Pushkin: 'Boris Chetkov in his own Words'.

Additional research: Hermione Crawford