With no connections or money, he was lost in the big city, but was fortunate to fall in with some other young men studying to take entrance exams for the well known Tavricheskaya Art School (now known as the Roerich Art School). At first he was intimidated by these big city boys, but in the end Chetkov passed and they did not. His massive work ethic once again stood him in good stead.

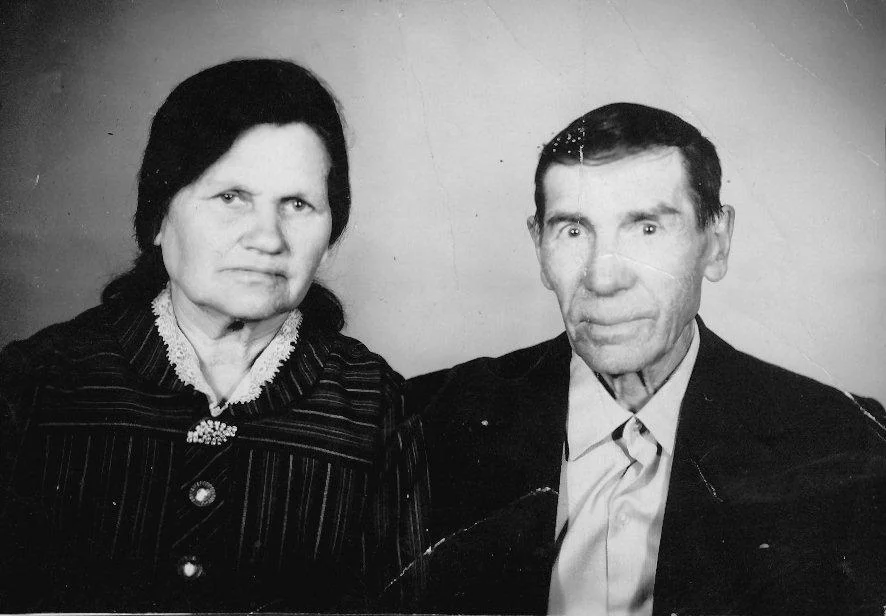

Sadly what should have been a glorious experience for the young artist quickly turned sour. In order to support himself Chetkov worked as a loader in a food warehouse. At the end of his first year he caught brucellosis, a very unpleasant, extremely infectious disease which causes high fever and muscle pain, and is frequently fatal. Chetkov wasted away in hospital, coming so close to death he was actually taken down to the morgue before someone realized he was still breathing. His parents took him back to their new home in Sverdlosk (now Yekaterinberg), and in a last throw of the dice, they paid the huge sum of 400 roubles (about three months salary) to the local vet (experienced in treating brucellosis in animals) to try and save Chetkov. Amazingly his potions worked, and the young artist made a full physical recovery.

However the long disease left a scar on his psyche. He was more single minded, less inclined to trust the world, more desirous of searching for deeper truths. What little mental reserve or boundaries left after his stark early life experiences were completely burnt away in the furnace of his passion to paint from the heart and soul. He had survived death: he was an artist on his own terms and only on those terms; he wanted to make every moment count.

“When I start working on a new project, I never think of work I have done before; I forget all the uncertainties, insecurities or inner torments. If I have a difficulty starting new works, say, two to three days, I would walk around my studio and look at my previous works as if for the first time, they are all forgotten to me. At exhibitions, many tell me that my works don’t have an identity, because they do not belong to any school, and all art should belong to a particular one. I don’t agree with this. To me, following someone’s teaching is like feeling trees or making shoes, boring. Art should be an experiment, without any set rules. No limits, no horizon; not many understand this.” Boris Chetkov

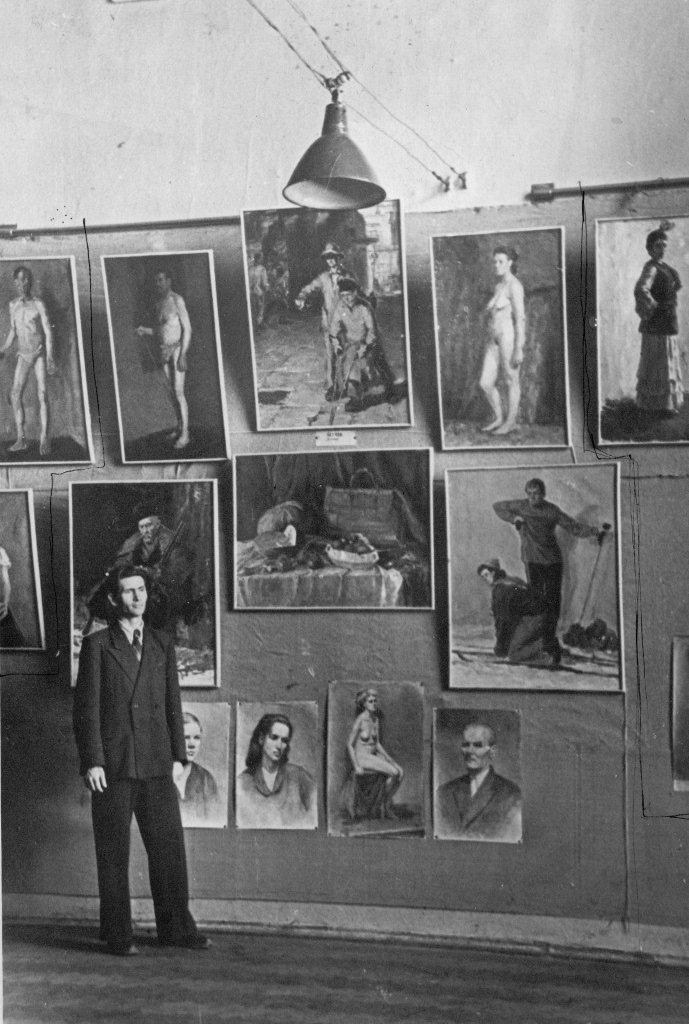

Chetkov did not return to Leningrad, instead enrolling in the highly respected Sverdlovsk School of Arts (now known as the Ural State Academy of Art and Architecture in Yekaterinberg). Here, slowly recovering, he studied under VF [or FK] Shmelev, who himself had been a protégée of Ilya Mashkov, one of the most prominent members of the renowned Jack of Diamonds avant garde group in the 1910s. (Years before, in a backwards echo, Mashkov had been thrown out of art school for being too ‘freethinking’)

Shmelev was so impressed by Chetkov that he took him under his wing and started teaching him independently. He told Chetkov that he should paint in a certain way, but never insisted on it – Chetkov described him as ‘free and easy’. In any case it was already too late to mold Chetkov into a specific school of painting (if indeed it would ever have been possible): “I had my own vision, I saw the world in a different way. I saw colors and relationships. It was too late, I couldn’t paint like they did.”

Chetkov was lucky with many of his teachers. While Socialist Realism was the only art genre allowed in Russia at this time, and indeed the only form of art taught, there was still a rump of pre-Soviet artist-teachers who had survived the purges of the 1930s. Chetkov’s free style was, if not encouraged, certainly allowed to flourish: there was space to grow under determined individualists like Eifert, Shmelev and later the master watercolorist Sergey Vasilyevich Gerasimov and avant-gardist Vladimir Vasilyev.

While studying in Sverdlovsk, Boris got married for the first time. It was not a success: he felt pushed into it by his parents and the girl, who told him she was pregnant. It was not true, though in the end they did have a son together. Boris spent two years dutifully working in a school in Sverdlovsk as an art and technical drawing teacher but he was not happy. He explained, “I told [my parents] that I didn’t need a married life, that it was rubbish for me. I always wanted to study and I didn’t want a wife.” Chetkov would later interrogate the concept of family and continuance in images such as Childhood of my Son, a wistful work describing an idealistic pre-Stalin setting that would have been far removed from the actual childhood of his son.

Courtesy Kenneth Pushkin: 'Boris Chetkov in his own Words'.

Additional research: Hermione Crawford