In 2006 Peter Hoffman, Jr. was walking up Canyon Road in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Strolling past the Pushkin Gallery, something vivid caught his eye. He found himself face to face with the most arresting piece of art he had ever seen: Self Portrait in a Top Hat, painted in 1987 by a Russian artist called Boris Chetkov. The passion that this work inspired in Hoffman would lead him to spend nine years amassing a large collection of Chetkov’s most arresting and beautiful works.

Self Portrait with Hat (1987)

On a fresh May morning in 2006, Peter Hoffman, Jr. and his wife Susan were meandering up Canyon Road in Santa Fe, New Mexico, quietly absorbing colors and forms pitched against each other in the row of gallery windows.

Walking past the Pushkin Gallery something vivid caught the corner of Peter’s eye. Colors so dynamic that captured his mind so fully he stopped in his tracks. He found himself face to face with the most arresting piece of art he had ever laid eyes on: Self-Portrait in a Top Hat. Painted in 1987 by the Russian artist Boris Chetkov, it threw a kaleidoscopic gauntlet down at Peter’s feet and seemed to say, “I see you – do you see me?”

What was it about Chetkov that grabbed Hoffman when so many other artists had not? He explains, “I had always been seriously attuned to fine art, and had amassed a large collection of mainly American Impressionists. These pieces were beautiful but increasingly I found myself disengaging with them. With Chetkov, for the first time in my life, I was looking at a painting that seemed to contain the entire spectrum of what a great painting could be – it was beautiful and visceral, thoughtful in composition and fluid in movement, it was skillful and intuitive and seemed to contain a unique vision of the world that was both private and connected to the deepest themes of human spirituality. It almost demanded me to engage with it. Chetkov recalibrated everything for me.”

It was love at first sight. A connection beyond language, of profound understanding, like meeting the magus who articulates all the things you know to be true but remain unspoken. In this moment, collector and artist found each other, and although they never met, began a unique relationship through art.

“Clearly I was looking at a portrait, but I was also having a dialogue with it, and that really threw me. It was so vivid and communicated his sense of self so clearly that it was like speaking without talking. Intelligence and understanding just screamed off the canvas, evidencing inner strength coupled with a wry sense of humor and independence of thought. When you look at that painting you see an artist self-validating, so poignant within the context of communism and artistic oppression, making a simple statement: “I am!” In that one painting, Chetkov established himself as a rare creative spirit governed by his own music and not the external notes played by others.” Peter Hoffman, Jr.

Sometimes it just takes one person to really understand an artist to change the way the whole world sees them, like Vollard’s comprehension of Chagall and Louisine Havemeyer’s love for Degas. Or, take Sergei Shchukin’s championing of Matisse. Starting in 1906, Shchukin bought 37 of Matisse’s works includingHarmony in Red (1908). Matisse may have revolutionized the art world by liberating color from form, but at the time it was said, “One madness painted them and another madness paid for them.” In 1918, the collector and his family fled Russia and his art collection was divided between the State Hermitage Gallery in St Petersburg and the Pushkin Museum of Fine Art in Moscow, two galleries Chetkov knew well.

“Just how powerful is art?” Simon Schama asks in his probing documentary series for the BBC, The Power of Art. “Can it feel like love or grief? Can it change your life, can it change the world?” In that first meeting, Peter Hoffman had the overwhelming feeling that yes, indeed it could.

THE FIRST FOUR ACQUISITIONS: PAINTING ONE, SELF PORTRAIT IN A TOP HAT, 1987

On that weekend in 2006, Kenneth Pushkin, appreciating Peter Hoffman was a serious collector, invited him into the gallery’s vaults and revealed a treasure trove of works from Boris Chetkov, who was still living in Russia. Before him was a virtual lifetime body of work, and as such it presented a rare opportunity. As Pushkin proceeded to tell the story of Chetkov and his subsequent discovery of Chetkov’s paintings, Hoffman’s eye wandered over the vivid work, trying to make sense of the find.

Several questions presented themselves to Hoffman. Firstly, how was it possible that someone living in such a difficult and challenging environment for much of his life could paint like that? The answer lay before him, represented in the large number of highly achieved and resolved paintings. They suggested not only great intellect and talent but also a phenomenal work ethic, independence and an irrepressible creative spirit. Additionally, he wanted to know how it was possible that Chetkov had remained relatively unknown.

Ultimately, and perhaps most importantly, Hoffman began to consider what it was about Chetkov’s paintings that gave them such magnitude, power, depth and relevance, surpassing anything he had previously encountered. Hoffman felt that these were not only great paintings, but also seemed to suggest a philosophy for living, one that might be applied to real life. The works transcended cultural, geographical, and political boundaries, each one unique, alive and beautifully painted, inviting the viewer to engage in the endless scope of Chetkov’s creativity. They touched upon an innate, profound, even mystical understanding of the energy and interconnectedness of all things.

Self-Portrait in a Top Hat characterized all that perfectly. The red line of crimson on his brow, powerfully supported by the cobalt blue in his eyes and imposing nose; the playful balance of peach and mint green in the top hat; the blocks of yellow, both a part of his face and of its surround, demonstrate the intuition and skill of a great colorist. Black accents and suggested outlines balance the compositional color without confining the face and highlight a fluent and dynamic brush strokes that gave the painting depth. Suggestive of modern masters before him, referencing Klee’s blocks of balancing color and Picasso’s distortion of features, Chetkov’s piece is less controlled, lacking overt statements of any school, created with a unique internal coherence. For Chetkov the essence of a subject, and how one experiences it in that moment, is more important than any specific rendering or exact likeness. He was trying to authentically express the complex nature of something.

Hoffman acquired four paintings by Boris Chetkov from the Pushkin Gallery that first weekend: Self-Portrait in a Top Hat, 1987; A Walk, 1992-1993; Cathedral of Vasili of Caessaria, 1994-1995; and Lilac Day, 2000. This initial acquisition seemed to encompass the depth and breadth of Chetkov’s virtuosity, representing his major themes (portraiture, equine art, landscape, genre and still life), mastery of color and dynamic composition.

This remarkable group of paintings triggered in Peter an intensive nine-year mission to acquire specific works that would represent in their totality a comprehensive catalogue of Chetkov’s artistic trajectory and development.

THE FIRST FOUR ACQUISITIONS: PAINTING TWO, A WALK, 1992-1993

A Walk (1993)

A Walk, one of the first four paintings that Hoffman acquired, is a masterful interpretation of an important historical genre – Sporting Art – which touches on themes of power, authority and grace. Chetkov’s work moves beyond the notion of a single authority mounted on a horse. A group of riders, shimmering with movement, emerge from the canvas. Beyond the wonder of its composition, it illustrates that power is something to be shared and is always evolving.

“At first glance we see three mounted horses, moving in unison from right to left, representing the essence of harnessed power and directional, spirited motion. Wonderfully, however, upon closer observation each horse and rider pulses with its own energy and rhythm, like different elements in an orchestra.”

Peter Hoffman, Jr.

THE FIRST FOUR ACQUISITIONS: PAINTING THREE, THE CATHEDRAL OF VASSILI OF CAESSARIA, 1995

Cathedral of Vasili of Caessaria (1994-95)

his idea of shared energy illustrated in A Walk is also deployed in Cathedral of Vasili of Caessaria and this is what resonated with Hoffman. “Even though the title of the painting suggests religion, the painting also speaks of spirituality. It is not a cathedral but an amalgam of structures, a timeless chain of cathedrals linking together and with the landscape around them. The composition is fascinating: Chetkov balances the density of color and form on the left with light and verticality on the right. To me it illustrates getting the balance right in life between religion and spirituality, rules and spontaneity, nature and manmade.” There is an abundance of energy and dynamism and yet he does not subordinate the painting to a uniformity of brushstrokes. It is a quintessentially Russian scene, replete with onion domes, but the color is not reserved for the cathedral’s rooftops – the whole canvas shares a dynamic wash of color. Nature itself is the cathedral.

Chetkov’s powerful color sense, one that both expands in the moment and transcends it, came to fruition around the period when he painted Self-Portrait in a Top Hat. It is relevant when looking at this aspect of Chetkov’s art to draw parallels with Matisse, not only with regards to his use of color, but in the continuing evolution of his artistic process, and ability to overcome personal hardships through creation. Unlike Rothko and Rodchenko, Chetkov resolved things in his paintings, and, in the words of Alexander Borovsky, Curator of Contemporary Art at the Russian Museum, St Petersburg, “[He] sought to enrich the color composition, looking at how to fill his color with light and setting himself advanced artistic tasks.”

Think of Matisse’s Chapelle du Rosaire de Vence with its brightly-colored, stained-glass tree of life illuminating the chapel’s bare interior. Primary colors bounce off the white walls and fill his monochrome outline of the Stations of the Cross with glimmering blues, yellows and greens. This was the apotheosis of his positive belief system. Working with glass is where Chetkov’s career first took off, as he experimented with filling it with color, stating, “Glass is fire. The material enchants, draws you in, and from the hot mass comes a work of art. The artist is dependent only on himself, like a magician.”

One could apply the above comment to his paintings too. He does not fill forms with color but coaxes and pulls them out using the colors. This almost alchemical awareness of tones and the way they connect to emotions was achieved through fearless experimentation and integrity of purpose. It was this aspect of his creative process that liberated him, each painting standing as a true representation of Chetkov’s inner state: his memories, his moods and his mind. “I began a new work, never thinking of what I had done before, utterly forgetting my experiments and all my agonizing.”

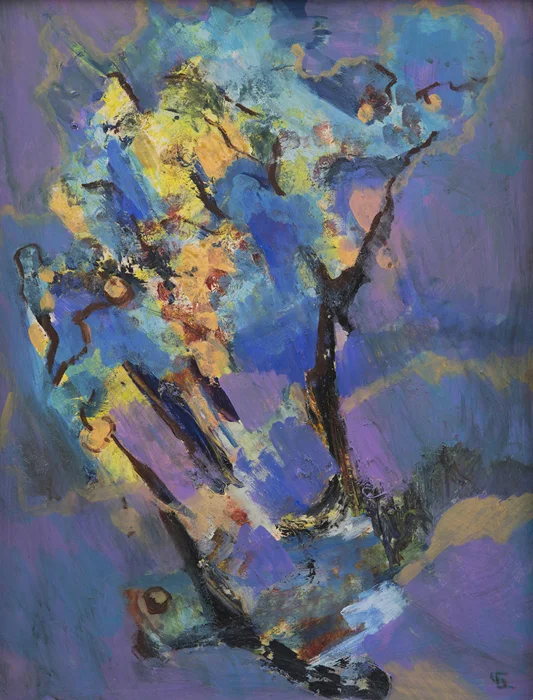

THE FIRST FOUR ACQUISITIONS: PAINTING FOUR, LILAC DAY, 2000

Lilac Day (2000)

One could apply the previous comment to his paintings too. He does not fill forms with color but coaxes and pulls them out using the colors. They undulate like fire, the painting drawing the eye in with contractions and out with expansions. This almost alchemical awareness of tones and the way they connect to emotions, was achieved through fearless experimentation and the utmost integrity of purpose. It was this aspect of his creative process that liberated him, and whilst he has been criticized for not adhering to one particular school, each painting is a true representation of Chetkov’s inner state: his memories, his moods and his mind. “I began a new work, never thinking of what I had done before, utterly forgetting my experiments and all my agonizing.”

Which brings us to Lilac Day, the fourth painting that Peter Hoffman bought after his first encounter with Chetkov on that bright spring morning. The pastel pinks and purples, greens and blues lean into the flame of yellow at the center of the piece. Hoffman says, “The first thing that got me was his incredible capacity to portray a moment and use color to articulate that mood, whilst clearly illustrating a clear spring morning – a subject that compliments the emotion.”

Upon reading the painting, noted architectural historian Alexandra Casserly remarked, “I think this painting may speak of the frailty of community and humanity and imminent change. The constant and conflicting movement within the piece suggests changing times. ‘Lilac days’ are to be remembered and are quickly gone – but it makes the fury of the changing future more enthralling by contrast.”

CHETKOV AND THE ARTISTIC ENVIRONMENT

Armed Man (1989)

In order to understand the importance of Chetkov’s work arriving in the United States in 2003, it is essential to consider the moment in which he started painting. It was the 1950s when great American artists like de Kooning, Pollock and Rothko abandoned painting ‘things’ for a new depiction of ‘feeling’. They were responding to Cold War anxiety, to a western world caught between the bomb and the supermarket, paranoia and distraction, unreal and manufactured. Artists fought back and tried to reconnect people with what was real: “Could art cut through the white noise of daily life and connect us with the basic emotions that make us human: ecstasy, anguish, desire, terror?” Mark Rothko asked.

Simultaneously, in 1950s USSR, the ‘official’ face of art was Socialist Realism – art devoid of individual expression that embodied the communist ideal. It is a great irony of art history that the Russian avant-garde that flourished at the turn of the 20th century, and was celebrated by the Bolsheviks who sought out artists to articulate their radical visions of a new future, was replaced by Socialist Realism.

The revolutionary spirit was embodied by poet Vladimir Mayakovsky and the artist Alexander Rodchenko, and pulsed with the energies of their time. Profoundly anti-mystical and suspicious of organized religion, Rodchenko’s objective was to steer art away from language of representation towards mathematical precision, from reflecting the world to reflecting a specific vision of it. Writer Maxim Gorky expressed Socialist Realism’s aims perfectly: “The artistic representation of reality must be linked with the task of ideological transformation and education of workers in the spirit of socialism.” It was a brave experiment that unfortunately meant creative energy was quickly stifled by political expedience, a revolution that gave birth to a new order arguably more restrictive than the old. When Rodchenko announced the ‘death of painting’ with Black on Black, 1918, he could not have foretold that this would actually become manifest. The politicization of art divided Russian artists into the binary camps of official and oppositional.

Chetkov began his artistic career in this environment, one that was disconnected from both its own history and the rest of the world. As neither a reactionary nor part of any underground movement, Chetkov had already suffered the consequences of expressing an independent spirit (he was sent to the Gulag at the age of 16). But regardless of trials or task, he attempted to do it to the best of his ability, always applying hard work, discipline and his own creative nature. It harked back to what he learned from his grandfather, who had so impressed the young Chetkov with his ability to prosper through hard work: seek your fortune but find it through industry and integrity.

“Creation is both thought and action, and in this sense Chetkov was irrepressible. Ultimately Chetkov’s nexus of discipline and creativity was manifest in his art. Though he felt pain and isolation, rejection and humiliation, these feelings and longings did not eclipse his art or his artistic process. Rather than hold onto them, he worked through them. Chetkov was almost Olympian in his capacity to navigate through hardship; working day after day no matter what the external world threw at him.” Peter Hoffman, Jr.

WHAT IS ART?

Composition 656 (1990)

So, we return to our primary question: what is art? And what can it mean? As we stated earlier, for Hoffman it was life-changing. “It had the effect of awakening my senses, switching on the lights, seeing things anew. Chetkov's paintings were so vital and luminous, so suggestive of all the things that seem on the periphery of our perception, and so complete that they engaged my total attention.”

In the fast-paced, hyper-global 21st century, the need to feel ‘in the moment’ has grown exponentially. Enter Chetkov, stage left, with his flamboyant color palette that speaks to our modern imagination, a lyrical and rhythmic composition in tune with our modern sensibilities, and an astonishing range of work offering a multiplicity of interpretation and understanding. “To me, this is what makes Chetkov such a potent and wonderful discovery, says Hoffman. “Imagine having a piece of art on your wall, reminding you every day to take in every moment and really see what you are looking at. To me Chetkov’s work is like my life coach, it urges me to dig deeper, look smarter, and be fully present.

“Everyday we are each faced with a choice – do we turn away from or turn towards our own truth? How do we make the choice without becoming so self-absorbed that we lose sight and respect for all things great and small? Chetkov had great mindfulness, he was self-aware not self-absorbed. By listening to his inner being which seemed to demand constant creation and experimentation he gave himself permission to realize his inner life without fear.”

It is this kind of passion, this kind of statement of intent, that makes the world open its eyes to a master artist. For Hoffman wants nothing more – and nothing less – than for Chetkov to gain the audience his art so richly deserves.

Nico Kos Earle